Should classic books be updated to delete or change words or passages that are or could be construed as offensive? Related, should modern authors compose their works with an eye toward not offending anyone? These are difficult issues with no easy answers.

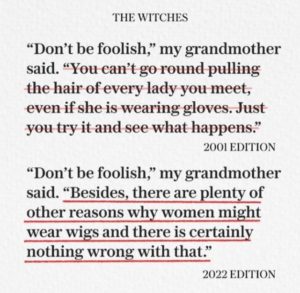

You may have read that Roald Dahl’s classic children’s books were recently “updated” (hundreds of edits) by “sensitivity readers.” Here’s one example from Dahl’s The Witches (the witches are bald so they wear wigs) that changes a passage from funny and interesting to unfunny and bland.

The original edition said: “You can’t go round pulling the hair of every lady you meet, even if she is wearing gloves. Just you try it and see what happens.”

The original edition said: “You can’t go round pulling the hair of every lady you meet, even if she is wearing gloves. Just you try it and see what happens.”

The revised, sensitive edition says: “Besides, there are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.”

In Dahl’s case, the author’s estate agreed to the changes, which perhaps makes the changes more palatable. Here’s one of many articles discussing the Dahl situation.

As Atlantic writer Helen Lewis noted, the problem of purifying Dahl’s works is he never wanted or attempted to be a “pure” writer. The title of her article says it all: “ROALD DAHL CAN NEVER BE MADE NICE; Rewriting his novels is about corporate safetyism, not social justice.”

We exist in a sad era of censorship from both the left and right. The left doesn’t like writing (or comedians or anything else) that might offend anyone’s sensitivities; the right doesn’t like writing that addresses so-called “woke” issues (exactly what that means I still don’t know). An author friend I communicated with about this issue said in an email:

The far right has, for decades, opposed sex education because they think it lead kids to have sex. They deal with this unavoidable aspect of human nature through denial and taboo. And for decades, the left has mocked and excoriated the right for that approach. Then the left acts the same way with its own set of taboos and they don’t understand why people mock and criticize them. Like the far right, they think, “But it’s for the cause. If you mock us, you’re mocking the cause, and that makes you bad.”

In fiction, the censorship isn’t limited to classics or children’s books. Most major publishers hire “sensitivity readers” to cleanse the works of current authors (much to their dismay) before anyone gets a chance to read them. As Lewis commented in her Atlantic piece, “Sensitivity readers … are a newly created class of censors, a priesthood of offense diviners.”

Perhaps because I was raised by a journalist (my mother), as a law student taking Constitutional Law, I was strongly in the camp of Supreme Court Justices like William O. Douglas and Hugo Black, who took an “absolutist position” in First Amendment cases. They believed that no government restriction on speech was constitutional, even clearly offensive speech. The First Amendment applies only to government restrictions on speech, not private actor restrictions, but I generally hold the same view regarding private speech restrictions.

Of course, there are exceptions. There always are. As James Thurber wrote, “There is no exception to the rule that every rule has an exception.” In law, First Amendment exceptions include incitement, defamation, and child pornography. Similarly, there are instances of offensive speech in fiction so offensive as to demand changes. One of the most shocking examples might be the original title to Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. You’ll have to search for it on your own if you’re interested. It was that bad. Fortunately, even in 1939, it never made it into the American publication of a book that arguably created the entire “locked room” subgenre of cozy mysteries.

But where do we draw the line once we start down the slippery slope? One of the changes to Dahl’s work includes an edit to Matilda, where a reference to the brutal antagonist Miss Trunchbull having a “horsey” face was deleted. Really?

I have this question for all novelists out there. Do you ever find yourself diluting your work so as not to offend anyone (readers, agents, publishers)? This question is probably worthy of a separate “writing advice” post.